The Psychology of Investing Biases - Part 2: History, Halos & Illusions

"In my last post, I mentioned Daniel Khaneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow

"In my last post, I mentioned Daniel Khaneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow

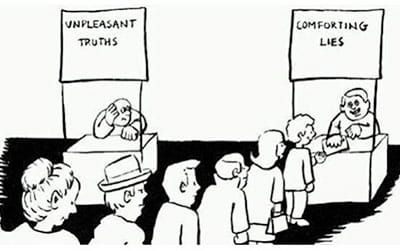

When it comes to investing in particular, we often place too much weight on the first system, when we really should be getting off our butts and employing the second more complex one. The reason is that System 1 often results in biases we aren’t even aware of.

Last post I discussed the first three biases of, overconfidence, social proof, and pride and regret. This post I’ll cover another three, leaving two for the final post.

The Halo Effect

Falling in love impairs our judgement — especially when we fall for an investment.

As strange as it may sound, investors often develop relationships with their investments. I’ve heard people say they want to watch a stock to see how it behaves, as if they will be able to predict its future movements. This is exacerbated when the investor likes and uses the company’s products, and becomes downright dangerous if they’ve already made a lot of money on the stock. When this happens, investors can develop real blinders, dramatically overweighing a stock until it becomes a risk to their own net worth.

A few years ago, a friend of mine told me he had all of his investments in two stocks — the company he worked for and a high-flying tech company. I begged him to diversify, but it was too late. He was blinded by the significant profits he had already made and by the tech company’s great products. The next time I saw him the stock was down 30% and he wanted to know how I knew it would fall. I didn’t, but I can spot a lovesick investor from a mile away!

Suggestion: Always focus on the asset allocation of your portfolio. If you have more than 10% of it in one stock or security, you should strongly consider rebalancing your portfolio to a more reasonable level. This will reduce the risk to your net worth.

Considering the Past (cognitive ease)

“Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

There’s definitely some truth to this famous quote, however, many investors place too much importance on it. Just because you know what has happened in the past, doesn’t mean you can predict how future events will unfold. This strategy often gives investors a false sense of certainty that can end up hurting their investments.

A few years ago, Toronto experienced several mild winters. Many people took it as proof that years with high snowfalls would be a thing of the past due to global warming. Enterprising snow removal companies began offering to remove an entire season’s snowfall at a low price, thinking it would be easy money. As luck would have it, 2013 saw an extraordinarily high amount of snowfall causing snow removal companies to lose a lot of money. This randomness highlights how blindly focusing on the recent history without seeing the bigger picture can be problematic.

Although it’s often a better approach, lengthening your scope of history can still be problematic — it won’t cover all the potential outcomes possible in the future. In his great book, The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb illustrates this point beautifully through the story of a turkey’s life. For about a thousand days, the turkey sees the farmer as his friend. The farmer feeds him, looks after him when he’s sick, and cleans up after him. Every day that passes is more evidence that that the farmer wants nothing but the best for him. However, on one fateful day, usually just before Thanksgiving, the turkey realizes that everything he ever knew, saw or experienced about the farmer was wrong.

Taleb suggests that similar to the turkey, we are prone to believe that if something hasn’t happened in the past, it won’t happen in the future. Although this line of thinking works most of the time, being vulnerably exposed to something just because it has never happened before has bankrupted more than a few investors over the years.

The point to be taken here is not that history isn’t relevant — it is! However, overly relying on history and historical trends to predict the future will catch up to you at some point. And the longer you get away with it, the more exposed you’ll leave yourself in the future — trust me, I know my history! J

Suggestion: Don’t assume that because you know what happened in the past, you’re able to predict the future. Remaining humble is one of the best lessons history can give you.

The Illusion of Diversification

A client once said to me, “Why don’t we put all of our money into the five big Canadian banks and be done with it?”

In his mind they were five big “blue chip” companies that at the time had done very well and were not only the envy of most banks around the world, but most companies, too. Although he was right that they were well-run companies and had been great investments to date, he missed a very important point. Diversification isn’t just about the number of securities you own; it’s about protecting against unknown outcomes that can derail your net worth.

Although the five big banks are separate companies, they are influenced by similar factors and react similarly in different environments. If something unexpected happens, they’re likely to be affected in the same manner. This could work out for the best, but it could also fall the other way.

If you were a hockey coach and all the best players you could pick were left wingers, would you only choose left-wingers? Or, would you pick players for each position, even if they were not as good as the left-wingers? There are many financial environments, or seasons if you will, on the horizon. By restricting your investments to securities that are thriving in a current financial summer so to speak, you leave yourself terribly exposed to a potential financial winter.

Suggestion: When building your portfolio, don’t pick individual companies or securities just because they are in favour or highly rated. Look for investments in various asset classes that complement each other and aren’t influenced by the similar factors.

My next post will cover representativeness and familiarity and scarcity, as well as some final thoughts on investment biases. If you have any questions about this series, feel free to shoot me an email.